One of the biggest aspects of raising cattle, besides feeding them and crunching the numbers in the name of keeping financial records and doing annual income tax paperwork, is that direct interaction–and dare I say relationship–between the person caring for the cattle and the cattle themselves.

For most of those who grew up around cows and think they “know” cows, this is something that’s always taken for granted. But for the novice cow-keepers that are bringing home their first bovine[s] that they worked so hard to find? Talk about intimidating! Just how does a first-time cow owner get over their fears as well as some negative perceptions, and begin the life-long process of learning to work well with their first bovines? I may have a few of those answers below.

A couple of months ago I was interviewed on Homesteady‘s podcast about this very topic, as well as about getting your first cow. If you’re really curious about what I actually look like (LOL!) and what I had to say, you can find Part 1 and Part 2 interviews on YouTube, and audio podcast on iTunes, Stitcher, or PodBay. I give my kudos to Austin for doing an outstanding job on this, and it was great to be on the show!

This post is somewhat of an expansion of that interview, as was my previous post So, You Want to Raise Cows… Where to Begin? You may call this an “unofficial” So, You Want to Raise Cows… Part Deux, where I take you from helping you decide what kind of stock to get, to now getting to know how to actually work with them.

When I say “work with” cattle, I mean the whole aspect of herding (some may call it driving), handling, calming, training, and generally just getting to know how cattle think and behave; what I like to call understanding bovine psychology and behaviour. Knowing how to handle cattle, as well as learning how to interpret their behaviour is just as important as understanding what and how to feed them. It’s a matter of your safety and theirs. It also really helps make the whole endeavour a much more enjoyable, low-stress “chore” that virtually eliminates (or at least should eliminate) that nagging sense of dreading the worst every time you have to go out to work with your animals. While understanding bovine psychology and behaviour is important, what’s even more important is what goes on inside your head.

With that, I have several things I wish to discuss in this blog. First and foremost is understanding your frame of mind when working with cattle. Little things like what mood you’re in and how you perceive the concept of working with cattle have far bigger consequences than you may think. These perceptions include the negative experiences you had or stories you heard or facing any fears you may have about these big, intimidating beasts. On the other side of the coin, the perception that cattle are so-called, “sweet, adorable, and won’t-hurt-a-thing animals,” as a dangerous concept that could land a person in the hospital, or worse, must also be discussed.

How to correctly interpret bovine behaviour and begin working with them will be the next installment of this two-part series; How to Safely Work with Cattle Pt. 2: Starter Stockmanship. Stay tuned!

How Do You Feel Today?

Are you in a great mood, or are you having “just one of those days,” where things are just not going your way?

This is an important question to ask yourself before you enter the corral. Your success with how well you are able to work with your animals largely depends on YOU.

It’s easy to make up the excuse that, “animals have a mind of their own and will do whatever they want whenever they want.” But that doesn’t mean anything when you are the one responsible for your thoughts and actions, and the inconvenient fact that animals, like cattle, are so incredibly perceptive.

Cattle are extremely sensitive to our emotions. Just snap your fingers and that’s how quick a bovine can tell what frame of mind you’re in. They pick up on whether we’re tickled pink or pissed off enough to want to throw a wrench at someone’s head. (Please don’t do this.) They’re also very good at sensing how tense, anxious, nervous, calm, happy, sad, stressed, worried, or excited we are.

Cattle have this innate ability to reflect back, in their own way, how we’re feeling. They aren’t smart enough to question why we’re feeling the way we are; they’re only able to take what we’re feeling and react according to how they perceive our own emotions. What’s fascinating about this is that this happens when we don’t even realize it. Usually, our big brains are too busy figuring out life’s materialistic problems to really connect on a much deeper level with our own emotions and thus be more mindfully aware of how our own thoughts (and actions) affect those around us.

Our thoughts, which determines our actions, that only each one of us has control over, has some huge consequences in how not only our animals perceive and treat us, but also the people in our lives. This can mean the difference between complete trust and respect to sheer avoidance and suspicion every time we enter the corral–or even a room.

You see, it’s a whole lot more enjoyable to work with cattle when you’re feeling good and relaxed about it all. But when you’re in a bad mood, or more importantly, the very thought of moving cattle today grants an eye-roll and a heavy sigh, and even a couple of curse words under your breath, then you’re basically asking for trouble.

Negative Perceptions Begets Negative Consequences

There’s a prevailing and albeit negative belief and attitude that I want to share with you about the very thought (even the mere mention) of moving cattle. It’s something that actually goes beyond just simply being in a bad mood or having a bad day.

See, as you all are quite aware, having a bad day just means that a lot of things on that particular day just aren’t going your way. We’ve all had those days. It’s on those days that you really shouldn’t be working with your animals–unless you just need to take the time to hang out and simply “be with” them, if it’s something that helps you calm down and relax some (I know it does me; I consider it a form of therapy). But if you’re not that kind of person, and you have to work with them or do chores or whatever with them, then there’s a possibility that they’re not going to make things easy for you either. In fact, they may just want to avoid you… or you may be made a bit angry that you end up doing something regretful that shatters the trust you’ve tried hard to build with them.

It’s just common sense to minimize or completely avoid, if you can help it, working with your animals–again, unless you find them a healthy source of emotional and mental therapy, just like your favourite dog or cat–when you’re in a foul mood. Go take your anger out on something else (NEVER someone else) like a punching bag or the door or whatever inanimate object happens to need a really good beating that nobody else will mind getting beat. Or, go for a walk, take a nap, have coffee with a close friend to whom you can vent to your heart’s desire and whom is more than happy to lend an ear and maybe lend a hand to help you out in your frustrating pickle; or whatever helps you blow off a bit of steam and make you feel better again, and not be a Stormin’ Norman that your cattle want nothing to do with.

Yet, if you carry some kind of negative attitude towards the very thought of moving cattle, you honestly do not have to be in a bad mood–nor have a bad day–to carry such hard feelings about working with cattle. You can be in a great mood and complain about such a mood being spoiled because you had to work cows today.

I kind of consider it a “bad habit” of sorts that’s been borne by generations and vast accumulations of bad experiences, freak accidents, train wrecks (figuratively speaking), horror stories and even the reason for husband and wife winding up hating each other and filing for divorce! Hell, this moving and working cows debacle is usually a subject of a variety of jokes among cattle folk, and has been noted in more than one country music song, such as Corb Lund and the Hurtin’ Albertans song, “Cows Around”:

//www.youtube.com/embed/_IW0qnnlCI0?wmode=opaque

Sure, it’s fun to joke about it, but in reality, it’s a far more serious issue. Honestly, if it wasn’t seen as such a serious issue then we wouldn’t have people like the late Bud Williams, like Temple Grandin, or Steve Cote, or Hand’n Hand Livestock Solutions’ Tina Williams (daughter of Bud Williams) and Richard McConnell, or other notable stockmen and -women doing their absolute damnedest to reach out to as many cattle producers as possible and teach them about low-stress cattle handling (also called proper stockmanship principles and practices).

I’m getting ahead of myself. The problem with this prevailing attitude towards working with cattle usually comes from negative experiences that folks are not all that keen to soon forget and put behind them. These experiences have been scary, very stressful, and/or “exciting” ones; or just some form of knowing (without feeling the need to question it) that the only way cattle can be worked and moved is the way that involves a lot of whooping and hollering and swearing and name-calling, not to mention a host of cowboys, ropes, dogs, quads (or horses), just to get those cows started to move from point A to point B!

That’s where you get all those fantastic stories–like that time when Tommy (or whatever his name was) had a “pissed off momma cow” come charging at him and he had to scale the fence to get out of her way, lest he get snot blown down his back pockets and some good bruises to show off. Or, that time when the big herd bull lost his sh*t and took out 20 feet of fence–or suddenly turned on the old cowboy driving him and busted up both the horse’s ribs and the man’s legs… or what about that time when the well-respected neighbour got himself killed by that one cow with the infamously nasty disposition that everyone else was told to keep an eye out for, but sadly poor ol’ Neighbour Bill forgot about…

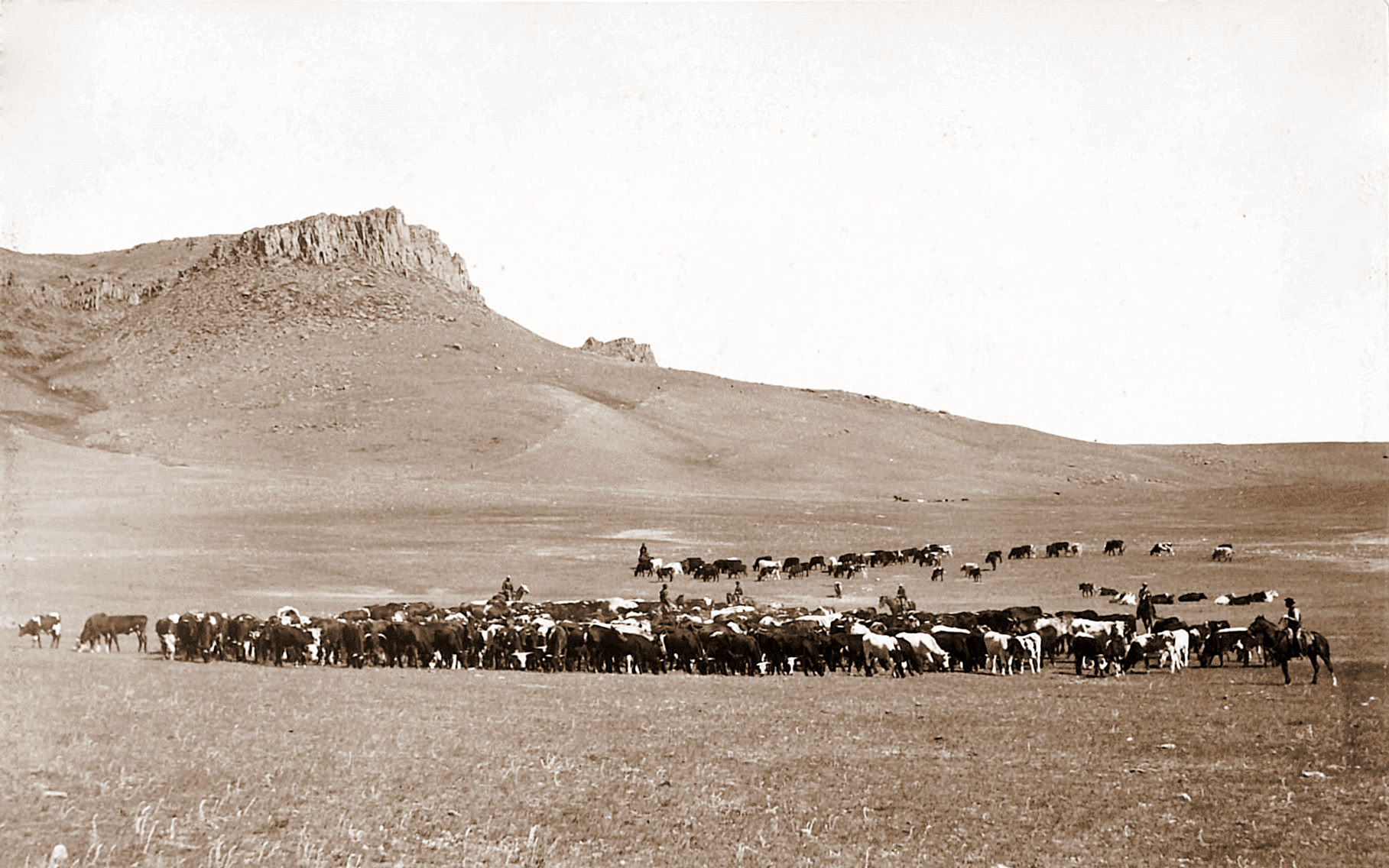

You can go back to the 19th century and find similar stories of this nature. The only thing back after the Civil War those tougher-than-nails war veterans-turned-cowhands had some really rank feral cattle to deal with. Back in just before the turn of the 16th century the Spaniards let loose a bunch of their cattle they brought over with them into the southern and western part of the United States and northern Mexico. Those Spanish criollos had about 400 years to adapt to some really rough country, and spread their numbers around. By the time the Civil War ended and folks were moving west, there was a huge demand for beef back east, and these cattle (and there were a large number of them, I believe historical records numbered them in the hundreds of thousands) were the best immediate source of beef to ship north and east. It was the job of those men to get those cattle to those markets and trains–easier said than done. Back then, most knowledge of proper stockmanship skills was largely unknown and unheard of to most of those men of the Old West who went on those very dangerous cattle drives.

Cattle drive at Great Falls, MT cir. 1890. From Wikimedia Commons.

Allow me to speak on a much more personal note in this section. I’ve known people who have had some very close calls, or who ended up in the hospital with some pretty serious injuries. On top of that, I’ve known people who have been killed by cattle.

My own great grandfather was killed by a bull a few decades before I was born. I’ve had my fair share of scary experiences, a couple of which were unforgettable and should’ve mentally scarred me for life, giving me a phobia about the very thought of working with, let alone being around, cattle.

Like that time when I was only 3 or 4 years old, and a yearling Charolais bull was feeling pretty lonely and left out, so he decided to make a break for it, and busted out of the wooden fence of our old “hospital pen” Dad was keeping him in. Unfortunately, I was playing by the fence, heard (and seen) the commotion, and tore off back to the house screaming bloody murder like a tiny banshee. Scared my Dad to bits! I think I gave that poor bull a good scare too!

Then there was the time that I was getting worried about my folks being gone for long, leaving me behind in the old farm truck right in the middle of the corral where the steers were. I decided to make a brave (and rather foolish) attempt to jump out and go looking for them. I was only around 6 or 7 years old at the time. As I ventured to the cattle shed, I was met by a red spotted-face (“brockle-face”) steer. He wasn’t too keen on my presence, and for my size and stature thought I was a two-legged predator about to give him trouble. He shook his head and charged at me! Now, little girls just can’t help by scream bloody murder (again) when they get scared like that, which is exactly what I did, proceeding by running away as quick as my little legs could carry me, back to the safety of that old farm truck. Fortunately, the steer figured it wasn’t worth the effort to chase me all the way there. But my poor parents sure came running right back to see what happened–and if I was okay! Boy, I was sure shaken up and crying pretty hard, but I was just fine nonetheless; I certainly earned a good lesson from the School of Hard Knocks!

I bring up these personal stories just to show that I too have had my share of negative experiences that honestly could’ve been carried with me to today. I could be sitting here and still thinking that moving and working with cattle is the most stressful, crappy job in the world. In the past, I’ve seen the way Dad had worked with the steers we had, using the same forceful tactics I gave mention to above (minus the dogs, horses, quads, other cowboys and ropes; it was a lot more chasing and yelling than anything from what I remember). I consider these too to be negative experiences in the realm of working with cattle. Where did he get that kind of attitude from? No doubt from his father, and his father before him, and so on. Really, just like my late Grandpa and Pa (my great-grandpa mentioned previously), as well as those old cowboys of the Old West, it was the only way he knew of working with cattle, giving rise to the mantra, “This is the way we’ve always done it.“

But from the bottom of my heart, I truly cannot fault him nor Grandpa nor ol’ Pa for not knowing any better.

I really wish to talk a lot more about negative attitudes towards working with cattle leads to negative consequences; things like why cattle are actually more dangerous than sharks, why people end up in hospital or in the grave from working with cattle. Briefly, I can state that the negative consequences are in the form that those animals can only take so much pushing and screaming at them before they turn around and give payment where payment is due, so to speak. In other words, if you keep poking the tiger with a stick that tiger will turn around and have you for supper. If you still don’t get that analogy, then stay tuned for another upcoming post on this very topic!

How do you “fix” these negative attitudes then? The answer lies in another personal story I’d like to share here.

Dad had never heard of Bud Williams nor Temple Grandin until a few years before his untimely death. At the time, I was in university taking an Animal Science major and through the courses there, getting introduced to and beginning to learn all about low-stress livestock handling (among other things). I thought these were just great, so I brought back some much-needed tips and tricks for him to implement, so as to make working with our backgrounder-stocker steers a whole lot less stressful than before.

At first, he was a little skeptical, not sure what his daughter had in mind when bringing forward this new yet fascinating information. I had to get him to do a bit of reading and watching some of Grandin’s videos before he relented and started doing things a little differently; such as putting up a tarp to cover the sides of the alleyway before the calves entered the squeeze chute.

Unfortunately, he died before any more major changes could happen, but I’m at peace with that. But the fact that he was so open to my suggestions and recommendations enough to start implementing them on the farm is very humbling for me. I think that if he were still alive today, the farm certainly wouldn’t be the same as it was back in the winter of 2007 when God told him had to bid us all farewell. Love you, Dad!!

Dad is an example of, in a way, “fixing” that negative attitude merely by getting to know what is better than what he already knew. Educating and teaching others about these “new-fangled” proper stockmanship principles really is the only way to help get over such prevailing beliefs; the first half of the battle, though, is realizing–acknowledging–that something is indeed wrong here; that there’s got to be a better way to do this. The other half of the battle is won by letting go of those past negative experiences, and then learning how to do better. Isn’t that a beautiful thing??

That’s how I’ve been able to move on from my own bad experiences. I learned to do better, and forgave not only those cattle for just being what they were, what they couldn’t help but be, but also myself for the screw-ups and mistakes that I made (and I’ve made a ton, believe me). If I can do that, so can you!

Now, for all you newbies getting through all of this talk about negative attitudes and such, and having gotten up to this point, I’ve this piece of advice: don’t allow yourself to be daunted–nor be all that shocked–by all of this. This is just a whole part of the mindset that you will no

doubt face as you get more and more into the crazy world of raising cattle.

But you’re probably wondering about that other negative mindset–the one that is based more on a fear of being in the presence of those big beasties; where the very thought of working with cows makes your palms sweat, shoulders tense up and your mind filling up with worries and all sorts of what-ifs. I may be able to help you out there as well.

How to Not Be Afraid of Cattle

Did you know that I co-authored a wikiHow article that goes by the same title? Check it out HERE.

That said, I will keep this section short and sweet.

Remember my two stories I shared when I was just a little girl, and I had the absolute schitzen scared out of me, twice, by cattle? Well, with such traumatic experiences, how am I not scared of cattle now as a full-grown adult?

Part of the reason is that I was forced to face my fears. I can’t remember exactly when, or how it happened, but I think I remember it was maybe a year later after that last incident with that steer, when we got a new group of calves (after we sold the last bunch), that I was “put back to work” so to speak to help Dad with them. He made sure I was on the other side of the fence, of course, until I was old enough and felt good and ready to get in the same pen as those steers and work right alongside him.

I’ve learned over the years that keeping calm and thinking of good things helps both the cattle and me. I’ve also learned that we tend to create the very things we fear the most. I don’t know why we do that, but we do it. And it’s funny how things work, because no matter what we do to prevent such a thing we’re so terrified about–and continue to be terrified about–it happens to us anyway. It’s like, what’s the point of doing all these things when the problem, in the end, is our own fear? Why not solve that problem (the “disease”) instead of going to all the unnecessary effort of treating the symptoms? Am I right?

So, in order to NOT create such problems, don’t be so damn scared of them. Don’t allow yourself to be so focused on the bad stuff that you completely overlook the good! That’s where the wrecks can (and will) happen. Just don’t even think about the bad stuff, nor worry about future events that may not even happen in the first place! Focus on the good, don’t be scared of the bad and the what-ifs, and good things will come. It’s that simple!

Here’s the other thing: People fear what they do not understand. I have seen many videos of people (non-cow folk usually) who do not understand how and why cattle behave the way they do work themselves into a big panic because they’re thinking (or maybe screaming), “THOSE COWS ARE GONNA EAT ME!” (being overly facetious here… for good reason) when those cows usually have something a lot less malicious in mind.

In order to stop thinking of such horrific things that likely will never happen, and to reduce such panicked feelings, is to get better acquainted with the bovine mind; get to better know their behaviour, the way cattle think; how they act; why they do what they do. Only then do you have a better chance of not being so fearful.

Master your feelings. Control your thoughts. Just like a Jedi master (if you’re any bit a fan of Star Wars like me). And don’t try, just do! As Master Yoda said: “Do or do not. There is no try!” The only way you can have such mastery is if you practice, practice, practice. You will not get it on the first go. A professional pianist never learned to play the entirety of Frédéric Chopin’s Etude Op. 10 No. 4 in one sitting, let me tell you! (I’m a big classical music nerd and a “novice” pianist myself, so forgive me for the reference and the completely unrelated video below for proof of context!)

//www.youtube.com/embed/oHiU-u2ddJ4?wmode=opaque

However, don’t allow yourself to become so fearless that you are one to mistakenly believe that bovines are adorable, super-sweet, big fuzzy dogs that won’t hurt a fly. That mindset in itself can land you in a heap of trouble.

Respect the Bovine

It’s all too easy to think that cattle are so docile and slow that they couldn’t possibly cause any harm. A person who’s only seen cattle behaving in such a calm, slow, easy-going manner, may think that that’s all they can do, and couldn’t do anything more exciting than that. In truth, cows are, for the most part, easy-going and much more interested in eating and socializing than stirring up trouble. And certainly, when they’re treated right and so socialized to a variety of people, they’re going to be so calm and quiet that it’s a wonder to think that bovines could be any different.

Truthfully, cattle that are calm and easy-going are the best to work with, as I may get to explain in the Part 2 instalment to this post. For one, they sure teach you patience! For another, they’re far less likely to take down fences or come after you if you push them too hard too fast. Calm, easy-going cattle are perfect for newbies just getting into cattle.

But my biggest beef–pun intended–with people and the concept of working with cattle is this mindset that cattle could never be anything but sweet, adorable, never-hurt-a-thing big beasties. For a lot of cattle, this really couldn’t be further from the truth.

Most cattle in this world aren’t raised nor socialized to be lovable house pets. Most cattle are far more acquainted with being around those of their own kind, and most any interaction with a human is a cause of some level of fear, be it mild or severe. This kind of fear in cattle is what can cause them to stay at least arms’ length–if not a bit further–from any human, even if it’s the person that is responsible for feeding them daily. It’s this level of fear where animals have this invisible “bubble” around them, which I will talk about more in the next post, that a person can use to move them around with.

What worries me about people and this mindset is that they often don’t realize how a cow or bull can suddenly turn on a person and do significant damage when enough of that bovine’s buttons have been pushed. A cow (or bull) doesn’t have to be horned to put a person in the hospital. Those heavy hooves and very powerful head and neck is enough to crush bones and cause internal bleeding. I’m sure we all know what horns are capable of, so I shouldn’t have to go into grim and gruesome detail with that.

Cattle can be dangerous for several reasons, one of which I mentioned above which often happens when they get cornered and there’s no visible escape route. Another reason is the lack of fear and respect bovines develop as bottle-raised calves. Bulls especially can be extremely dangerous if they’re raised as bottle babies, and kept as a pet; especially when the person raising these animals aren’t familiar (or just completely ignore due to complacency) with the particular warning signs and challenging behaviour a bull will give when he feels he’s being challenged.

I have yet another video to share. This is a full episode from Animal Planet’s Fatal Attractions, where one story described how one man was killed by his own pet bull.

Dairy bulls are some of the most dangerous cattle out there. Most of these bulls have been bottle-raised, and due to intense genetic selection for cows to be very feminine and very high milk producers, they have the genetic aptitude to be very testosterone-driven to the point that anything and anyone they suspect is a rival to their harem of heifers deserves to be waged battle with. One word to describe these bulls is “crazy,” and that’s not just me saying that. I’ve heard many a dairy herdsman say the exact same thing, along with an expletive or two, about such Jersey and Holstein bulls.

If you want another example of how dangerous cattle can be, look no further than the Spanish Fighting Cattle, which have been bred for generations to be agile, athletic, fast, powerful, and very dangerous. Even rodeo bulls can get pretty dangerous, usually when they’ve got so much adrenaline pumping in their veins from doing their job in the rodeo ring that they find some sort of excuse to go charging after a cowboy or rodeo clown.

When else could cattle become dangerous? Two other instances come to mind:

- When a cow has given birth to a newborn calf, and her motherly instincts are in full gear that prompts her to protect that calf with her life. The first few days to a week after a calf is born is the most dangerous time to be working with a mother cow and her youngster.

- A herd bull (or two) with one or more cows that have come in heat. Bulls with the cows get very protective and possessive of their girls, making them a bit more of a challenge to work with. While it’s great to have a bull who’s very committed to his job, it’s not so great when all he has on his mind is sex and not being co-operative with you!

It’s important to respect the bovine for what they are. Bovines can seem passive and slow, but when they’ve got a reason to be anything but, they can turn on a dime and react so fast that we’re often left in shock wondering what the hell happened… if we are lucky to live through it, as most of us usually are.

Complacency can kill, as the last video above should’ve clearly demonstrated to you. Don’t allow yourself to get complacent around the cattle that you take care of and see every day.

On the other hand, if you treat those animals very well with kindness, respect, and yes even a little bit of love in some way shape or form, they will reciprocate that level of positivity to you. Just remember that they’re still much bigger and stronger than you ever will be.

On to the next…

On that note, it’s well past time we turned our attention to the next instalment of this two-part series, where I talk about understanding bovine behaviour, pressure and flight zone, and how to get your first animals acquainted with you and their new home.