It’s hard not to think about proper stockmanship as something akin to a dance. There’s a lot of give-and-take involved, and in most cases, both parties enjoy each other’s company, flowing and moving cohesively as one.

In this second instalment of the two-part series How to Safely Work with Cattle, I move away from the “human mind” part of the proper stockmanship equation, where I talked about the different negative perceptions and emotions a person might have when working with cattle, and how to get over them. Here we shift into the fun part of being the “bovine interpreter,” if you will, where we look more at the “bovine mind” part of the stockmanship equation.

Interpreting bovine behaviour comes with its challenges. It’s not as easy as learning a different language; it involves us moving away from our unconscious predatory instincts and more into the prey-animal habits that may feel “unnatural” to our genetic make-up as a predatory species. Even learning Cantonese and its 2500 characters would be less of a challenge than learning to really think like a cow!

However, it is my strongest belief that bovine behaviour is a concept that every single person who regularly interacts with cattle should know. (This includes those European folks who often go walking on designated public walkways of the European countryside that run into cattle pastures.) The context for doing so is a matter of safety, our own sanity, and also keeping healthy relationships with our neighbours, friends, and loved ones.

The Art of Understanding Bovine Behaviour

The cryptic language–and it should be called such–of a feeling, sentient, and intelligent animal such as the bovine is, at least to us, much more silent than the kind of language that we carry on with. While body language for us is sure important, we rely much so more on verbal communication than anything. With cows, their form of verbal communication is, as of yet, largely unknown to us; it’s also not nearly as well-developed as what we’ve been able to master with practice over many generations. The bovine version of “talking” is a variety of “moos;” lowing, roaring (or bellowing), growling, bawling (like the “mmehhn” of a young calf), and calling. How they talk and what they say depends on the situation and what they’re feeling at the moment.

That is why we commonly rely on our ability to “read” the body language of cows and cattle in order to better assess what they’re trying to tell us (or other animals or each other) in terms of their intentions and even emotions.

Ethology (the scientific and objective study of animal behaviour) can make it seem like bovine behaviour is a dry and boring subject; however, there’s an inherent beauty and art form behind studying and thereby understanding bovine behaviour. Think of it as meeting a variety of different people from different walks of life. Unless you live under a rock in the middle of nowhere all your life, we’ve all met different people with different personalities. Cattle are not much different. Individually, they’re as varied and as different shade of colour as the next, with different quirks that make them just a little bit more unique than the next bovine. The beauty behind the art of understanding bovine behaviour is acknowledging the fact that how one cow responds to you doesn’t guarantee that the next cow will respond to you in exactly the same way!

For example, one cow may not like having you so close to her, so she responds by running away or if cornered, defending herself by coming after you. Another cow may not be nearly so nervous and shy and is perfectly comfortable with having you at half the distance of her nervous pal. Some cows are shy, others are extroverted; some are quite bossy, and others may be so laid back they don’t mind being in the middle of the pecking order.

With that, I want to discuss the fairly noticeable (and maybe not-so-noticeable) types of bovine body language and what it may tell us. Following that, I will touch a bit on the “pressure zone” and “flight zone” and how to use them in some very basic herding tips and tricks I’ve learned myself over the years. (I plan to expand a whole lot more on herding and other concepts involving working with cattle in future blog posts, so stay tuned!) A variety of tools to use to help you better work with your animals will also be good to know.

Interpreting Bovine Behaviour

Did you know that there are actually four different categories of bovine behaviour? They are as follows:

- Social organization/social hierarchies (“pecking order”), leadership;

- Mating/sexual behaviour

- Maternal behaviour (between momma cow and her calf)

- Abnormal/atypical/stereotypical behaviours

At some point in the future, I may write about these behaviours, but for the most part, and especially for this blog, my main focus is on the social hierarchical behaviour.

As stockmen who are much more interested in “working with” cattle as in herding them around, we’re more fascinated with how cattle behave in terms of how they function socially. At this point, I’m not interested in talking about mating habits, nor about how momma cow takes great care in looking after her calf. Of course, these are social behaviours too, but not in terms of the infamous pecking order!

See, the act of interacting with bovines is, in some way, a form of working in the realm of the bovine social dominance order. You’re goal and intention is not to act in the predatory role, but rather as being “part of the herd,” particularly as the two-legged “Boss Bovine” to be both respected and trusted. However, your goal is also to watch your animals to see who is near the top of the pecking order, and who’s falling behind in the leadership role.

The Bovine Pecking Order

I’ve found the easiest way to watch who’s who in the social hierarchical order is to just take a bit of time out of your day to literally do nothing else but hang out with the herd. I don’t recommend bringing a beer, a lawn chair and a book at this point because you’re going to want to move around a little bit now and then, and pay close attention to your animals. Please keep in mind the tips and tricks I shared in How to Safely Work with Cattle Pt. 1: Mental Preparations about keeping calm and never allowing any negative thoughts to cloud your mind.

The most opportune time to see who’s dominant and who’s subordinate is during feeding time, or when animals are grazing together. You won’t be seeing any particular dominance hierarchical status shown while they are resting; cattle tend to care a lot less about who’s dominant and who’s not when it’s time to relax and chew the cud.

Dominance and subordinate status tend to change and fluctuate with herd dynamics. According to some studies done, these shifts in a hierarchy tend to change more in cow herds than in a group of young feeder cattle that are already grouped in similar age, weight, and size. Cows that get thinner and less robust with age are more apt to be dominated by the younger, stronger, more sizeable cows. Often, the bigger the cow, the higher she sits in the social hierarchical chain. However, a cow with horns is more apt to be dominant over polled members of the herd due to those two sharp pokey things that really hurt when she’s forced to use them in a head-butting match. This is no different with bulls, steers, and heifers.

When in a mix of bulls and cows, usually the bulls are the dominant ones, simply because they are bigger and stronger than any of the females. Young bulls (or steers) and heifers get into physical matches where they establish hierarchies amongst themselves. As a result, often those males win that dominance game.

Cattle also always tend to pick on the weaker members of the herd. Sickly animals are ones that tend to be the last to the feed station, and the stragglers to the next pasture move; they are always getting pushed out of the way of the best feeding spots, and ones less likely to spend more time eating than the more dominant ones. When I was doing my regular pen checking, I could really tell which animal was sick just by how lethargic and lagging it was during feeding time. This one which was off by itself, or last to get up, or laying down by itself while the rest are standing and eating, was a cause for concern.

Cattle are not the type to use their mouths to bite nor their hind feet to kick out like all equines are infamous for. Nor do they rear up and strike out with their front feet as both equines and cervids (moose and deer mainly) do. Instead, they use their heads and their brute strength to get their way in the bovine social hierarchy.

When it comes to fighting for or establishing dominance, there’s a ritualized methodology they always use that always occurs in sequence:

- Approach

- Threaten

- Physical contact

- (Last resort) Fight!

- Chase

The approach usually is a rather subtle, stiffened pace, with the head held a little higher than the subordinate’s, eyes and nostrils wide. It’s less common as a full-on charge, especially bovine-to-bovine. (Often a charge–real or bluff–occurs after the aggressive threatening pose, not before.) I’ve also noticed an intense stare-down by the dominant animal, particularly if the subordinate can see the dominant animal’s eyes.

Aggressive threatening is not only that deadly intense cold stare (widened eyes and showing the whites of the eyes) but also the posturing. Posturing is almost always showing of the side and arching the neck and shoulders to display how big and strong a bovine looks. (I personally had a big bull do that to me several years ago.) This usually transfers into a lowering of the head to tuck in the chin and expose the poll (or horns), which is often closely followed by further approaching into physical contact. Usually, the dominant animal displays this; also, this threatening can be so subtle or occurs so quickly to our eyes, that we may not observe it as readily.

Making physical contact by swinging the head up to strike the other animal’s chin, jaw, neck, shoulder or ribs is often when either the threatening phase didn’t work well enough, or the subordinate didn’t see the other animal do their posing and approaching. In most cases, if the subordinate isn’t feeling up to putting up a fight away, that is enough to deter any further confrontation. In a lot of cases as well, a mere stare or very brief posing (that looks like nothing to us if we’re not watching intently enough) is sufficient to get a subordinate to quickly back off and move away. The importance of physical contact is trivial when this happens.

But what happens when the subordinate has had enough of being so low on the pecking order, and physical contact is just the necessary bomb set off to start a shoving match? That’s where the fight begins.

And it literally is a shoving, head-butting match of brute force. At times it can be deadly. But most of the time the match that involves a whole lot of spinning at the head-force contact point, backing up by the one being shoved the hardest and pushing forward by the shover, and head-butting followed by even more pushing and shoving results two animals that have established a new hierarchy (or re-established an old existing one), with a little bit of bruising but both alive and well enough to go on with the rest of their day.

Where it gets deadly is usually between two evenly-matched bulls who are so equally determined to get their way in the hierarchy that the fight for dominance becomes a fight for life. It can get so bad that animals can get gored (the worst-case scenario when it involves two horned bulls), or get broken ribs, and fall down exposing their wind-pipe to be crushed by their very aggressive and testosterone/adrenaline-fuelled opponent. It’s extremely, extremely rare for such hierarchical fights to get deadly among cows or heifers (or even steers), thankfully.

It also gets deadly when a human is at the receiving end of such aggressive confrontational actions. Usually, however, the cause of these incidents is by sheer human stupidity or someone who let themselves become far too complacent around these large and potentially dangerous animals.

The last stage of the bovine hierarchical challenge is the chase. The chase always happens after the fight is over. It’s the subordinate’s way of saying they’re succumbing to the dominant status of the animal that just beat them, and the dominant animal’s way of saying that they’re the dominant one and dare not be challenged again… for the time being. The chase may be short-lived, or it may be several minutes long. The one chasing tends to carry their head a bit higher than the subordinate one being chased, unless [s]he noticed a sign from the chasee that another challenge to meet head-on was about to happen!

How does any of this translate into the human-bovine interaction that morphs into stockmanship principles? It’s quite simple, however, it takes a little bit of time to explain. But first, check out the video below of a couple of cows duking it out for dominance.

//www.youtube.com/embed/ZTsYv2d9mCw?wmode=opaque

Where Humans Fit in the Bovine Hierarchical Matrix

The bovine pecking order involving the human element (us) is a little bit more complicated than just the bovine herd by itself.

We’re usually not there all the time; we’re present typically only when it’s feeding time, or when we have to move them from one paddock (or pasture) to another. We sure don’t look like a bovine, nor do we act like one. We’re the two-legged, forward-facing-eyed, hairless (save for what covers the top of our heads) freaks that give them food when we can see that they’re hungry, then we quickly disappear to not be seen for hours or days, later.

Bovines must think we’re really weird. It’s no wonder they have to line up at the fence to stare at us and wonder what in the hell are we even doing.

Yet they regard us with a bit of fear and apprehension; some more than others. They’re quick to move away should we approach; in some cases, if it’s someone they don’t know, they’re more likely to run for the hills than stick around.

It’s because of our predatory nature that the human-bovine relationship is a bit complicated. It’s totally natural for prey animals, such as cattle, to move away when a predator approaches them. So, they instinctually treat us like a typical predator, not someone with stockmanship skills. At that point, we’re not part of the bovine hierarchy, but an “enemy” of a bovine kind, regardless of who’s keeping their bellies full.

Sometimes, when we’re seen as such an “enemy,” we’re challenged in the same manner as a subordinate who dares to challenge a dominant animal’s status: approach, threaten, and move in to make physical contact if we’re paying them no heed to their warning signs. (Sometimes the first step isn’t even necessary if a person is close enough for a bovine to just go right ahead and make a threatening posture.) Some people are lucky to escape; others not so much, like my late great-grandfather.

Yet, when it comes down to proper stockmanship principles, we as humans are making the effort to make ourselves as not the mortal predatory enemy so much as that two-legged hairless freak who has worked hard to gain the herd’s trust and respect as well as the understanding that said hominid freak means them no harm and is Friend, not sworn and feared Enemy.

In order to convince those bovines that the particular human in their midst is a friend, that human must herd them; drive them. Work individually with them, moving them from one spot to another to another and so on. Just hanging out with them works wonders as well.

My “hanging out” strategy is basically just letting them get to know me; via my (calm) actions, my scent, and me being actively mindful of respecting them, their space (when it’s necessary), and their very existence. I don’t do staring contests nor make eye contact; I don’t try to chase after them; I also don’t move fast, and make sure I’m cognitive of when I must stop what I’m doing to all them to settle down if they’re still feeling nervous around me.

But when it comes down to establishing myself as the dominant one, hanging out doesn’t exactly cut it. Not especially when introductions are being made and the first question cattle have on their minds is how worthy of a leader are you… are you truly calm and assertive (the makings of a good leader), or are you actually more of a neurotic chicken-shit than what you convinced yourself to

believe?

My objective to establish myself as the dominant one is without physical confrontation. I have to use psychology to basically “subdue” (for lack of better terms) an animal that’s five to over ten times my size. That means having the courage to stand my ground, making no eye contact, until the animal decides to move off. I then follow through (very important) with “the chase” where I just herd the animal around until I see that my intentions have been made very clear to the chasee. Often times “the chase” begins almost right away, and that’s where it takes diligence to keep going until they settle down and are walking easy, not trying to run away when you’re herding them around.

It’s a complicated relationship, you see, as we’re naturally going to be acting as predator and moving animals around like a predator would, even though we don’t want to engage fully as a predator would because of the goal to keep animals calm and relaxed and not get in a big panic. Also, we probably are seen as “part of the herd” even though we’re not around as often as the rest of a bovine’s herd mates are, even though we’re a completely different species with different behaviours, instincts, and eating habits, and even though we still can be seen as a predatory species as we walk a very fine line between enacting on such instincts (which is super easy to do) and learning to work with our animals using proper stockmanship skills (which is much harder to do).

So, how do we go about pursuing the hard-won job of good and proper stockmanship? It all starts with understanding the pressure and flight zone of the cow.

Flight Zone: The Key to Moving a Cow

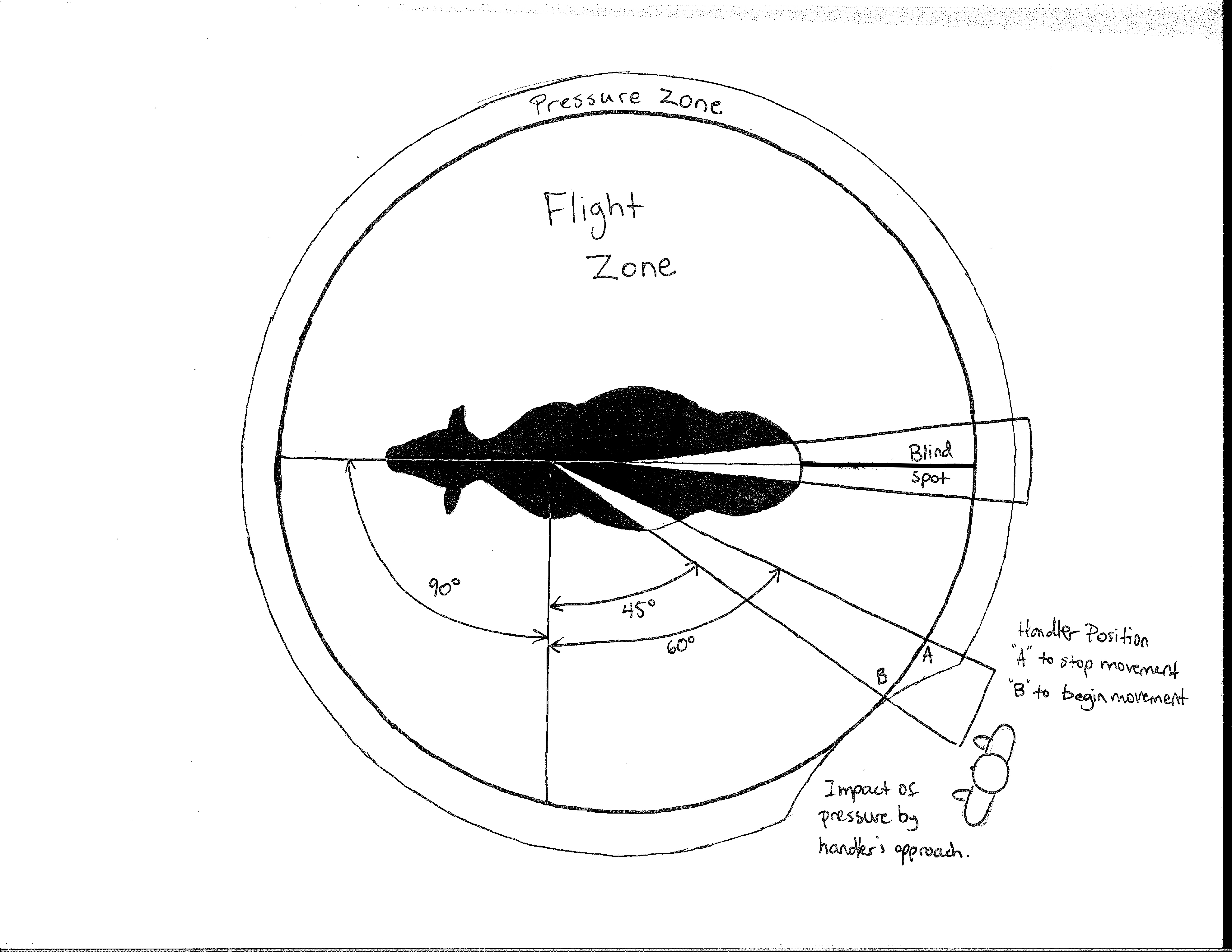

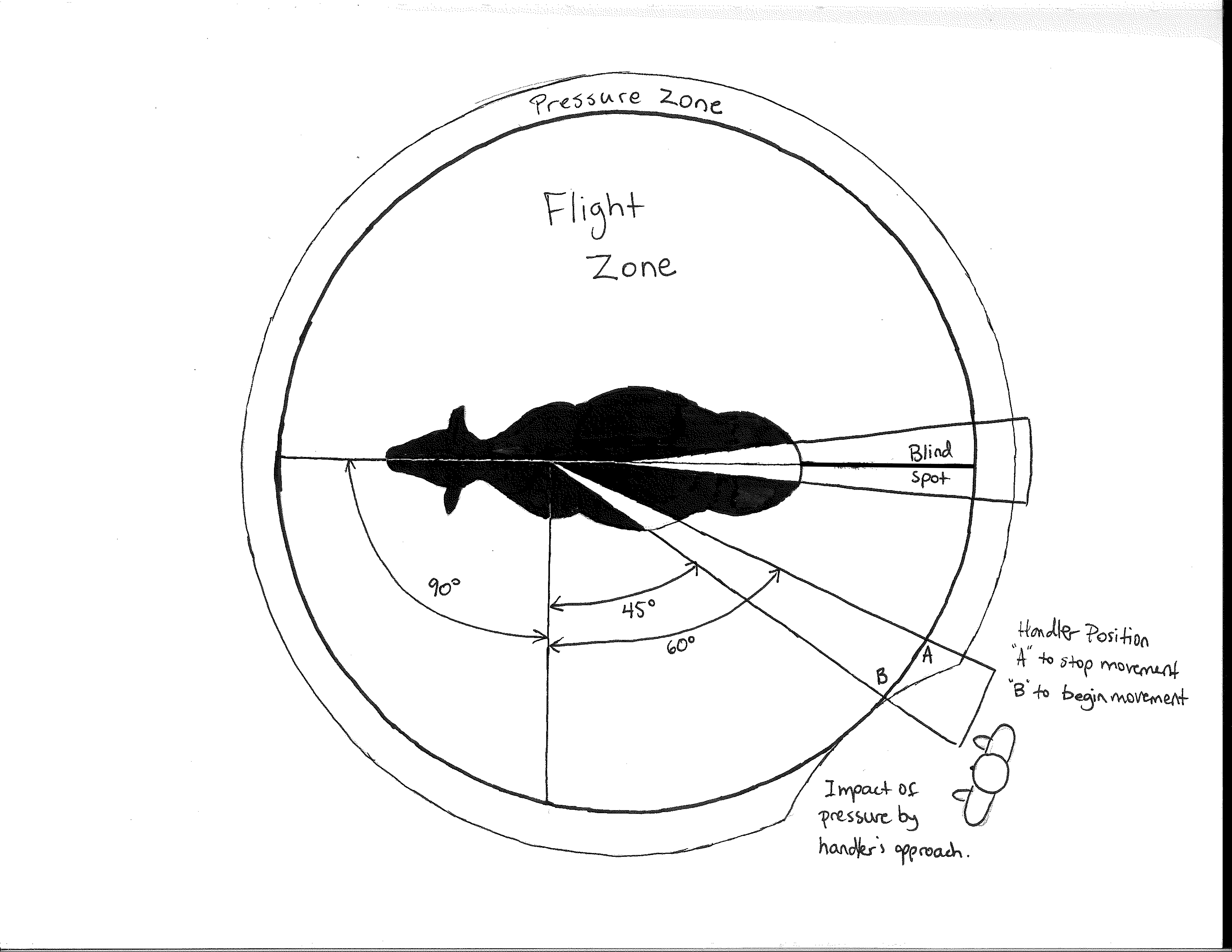

No doubt you’ve probably seen many versions of the above diagram numerous times before, like the one I sketched out for you. This diagram, in particular, is important because I wanted to show you both the pressure zone of a cow, as well as the flight zone. Most diagrams only show the flight zone, which is fine since its job is to demonstrate that invisible “bubble” cattle have in response to a handler or a predator. But that pressure zone shouldn’t be ignored, as it has its significance as well.

The “pressure zone” is the point just beyond the flight zone where the cow is beginning to feel uncomfortable with your approach, but not all that keen to move away just yet. Despite what I drew out for you in the above diagram, that pressure zone can be much broader than depicted, or it can be very narrow. It depends on the bovine, what previous experiences she had, what kind of environment she’s in, and how she feels about the person working with her.

A great way to tell if you’re in the cow’s pressure zone is just how attentive she gets the closer you move towards her. You may inadvertently walk right into her flight zone as you do so, but typically you will be able to notice the more attention she pays to you (ears perked towards you, intently looking at you) the further you walk into her pressure zone and closer towards her flight zone.

The “flight zone” is the area surrounding an animal that, when “touched” by a person or predator, causes the animal to “flee” and move away from the pressure applied to them. Just as with pressure zones, each individual bovine will have a different flight zone. One cow may have a flight zone with a radius as close as a few inches, whereas another may have as much as a radius of 30 yards or so. Such variances depend on previous experiences, how accustomed they are to having a person around them, and what kind of stressful (or not) environment they’re in.

Flight zones are one of the most important means of working with cattle and getting them to where you want them to go in as safely and calmly a manner as possible. No yelling or crazy arm-waving required!

However, working in the realm of flight zones has a very important limitation to be well aware of. This is the blind spot of a cow. A cow can only see 340˚ around her. (Just so you know, this is exactly the same deal with bulls, heifers, and steers!) In other words, she cannot see directly behind her. Thus, if you’re trying to apply pressure from directly behind, she will not be able to see you unless she turns her head–or whole self–around to be able to better see where you are. This can really slow things down, and cause a bit of frustration on your part (which you should fault yourself for doing, not the cow).

Thus, make sure you’re standing where the cow can see you and where you can see her eye. That means standing at an angle to the “point of balance” in order to move her forward, or even backwards.

That point of balance is found at the shoulders. Basically, if you move at a 45˚ angle towards her from behind the shoulders, the cow will move forward. On the other hand, if you move in towards her shoulder from the front at the same angle, she will back up. Coming directly towards her shoulder usually causes her to move away at a right angle in the direction you are already going, although I don’t recommend doing the latter as it can actually cause confusion on the animal’s part and misdirection of movement.

What about any other angle except that magical 45˚ behind the shoulder?

The best rule of thumb I can give you is that the more acute of an angle you are to the point of balance, while still remaining behind her shoulder, the more likely she’s going to move off and away from you. On the other hand, the more obtuse of an angle you make to the point of balance while still remaining behind her shoulder, the more likely she’s going to move at an angle in front of you.

Moving at a 45˚ angle from the front towards the right shoulder causes a cow to move off to the left. Moving towards the left shoulder from the front causes her to move off to the right. Moving right towards her nose causes her to back up.

Sounds pretty simple, right? Here are a few more:

- Moving directly parallel in the opposite direction a cow is going will make her move faster.

- Moving directly parallel in the same direction a cow is going will make her slow down or stop.

- Never work animals in curved lines. Always walk in straight lines with purpose and confidence. That includes making zig-zags to get a herd moving and to drive them.

- Learn to stop and back up. This causes a release in pressure, animals to slow down or stop, and/or to draw them to you.

- Never push from behind, and never “head them off” to try to stop them. That natural, predatory instinct will cause more headache than you think.

Now that you have a basic understanding of starter stockmanship skills, it’s time to look at what kind of tools to use when working with cattle.

Tools of the Trade with Good Stockmanship

The tools you may need depends on the situation and what you feel comfortable with using.

Stock sticks, walking sticks, or just any old stick you found in the bush that looks sturdy enough is one good tool to have on hand. A stick in hand may be just good support for you as you walk along, or a necessary tool to defend yourself if and only if it’s necessary. Think of it as an extension of your arm when you need to poke a bovine to get moving if you’ve got one particular cow or bull that has too small of a flight zone to do anything for you.

For some people, just having a stock stick in hand gives a sense of confidence that not having such a tool in hand lacks. This may be when working with larger stock, or horned stock, or any kind of stock that may make one a bit more nervous than usual. Can’t blame them.

Paddles are basically modified oars that have pebbles in them that rattle noisily when shook. These are handy when working with animals in closer quarters than the open corral or pasture, and when mistakes like getting in an animal’s blind spot are much more apt to happen. Though because cattle’s hearing is much more sensitive than ours, a sudden shake of the rattle is enough to cause a bit of excitement and fast movement, which may (or may not) be good in a situation when you should be trying to work cattle in a calm, quiet environment.

Finally, is the electric cattle prod, also called a “hotshot.” This battery-operated tool has two metal prongs at the end that, when the batteries are hot and electrical connections are good, can deliver an electrical shock that’s not quite as intense as that from a Taser, but is enough to get animals moving quickly. Cattle prods should be used as a last resort and in a handling facility where cattle are baulking and refusing to move forward. One shock to the hip or shoulder (never to the face) is usually enough to get that forward (or backward, if needed) movement down the chute.

Like with any tool, I strongly caution you on using it to beat or harass an animal. You could get yourself hurt doing so, and create a far more stressful environment than I do hope you first intended. Use these tools with the mindfulness that you yourself are the biggest influence and reason for how animals respond and work with you, not the tool that you choose to have in your hands.

At the End of the Day…

It’s up to you and you alone to not just be open to learning about how bovines behave and how the interact with you, but also how you can do better to make working with your animals as stress-free, safe, and calm a job as possible.

Bovines are more intelligent and complex creatures than we can eve realize. I haven’t even scratched the surface with what bovines are like beyond the simple manner of bovine politics and hierarchical status. It’s your job to understand that these seemingly slow, lumbering creatures are very much in tune with you and quick to react according to what they feel from you, and to always be mindful that they’re the ones who are going to teach you a thing or two about proper stockmanship, not me nor any book or on-line article you can read about stockmanship principles.

This is just the beginning. It’s going to be one helluva journey from here.